Uccello and Carravaggio had it down 500 years ago

As a boy growing up in London I lose count of the number of visits I made to The National Gallery in London. Whether going through my Impressionist period, High Renaissance or early Renaissance, there was always something there to fascinate and to intrigue. While photography had always been my first love in the visual arts, I think I learned more about seeing from gazing at the art in this great collection than from any number of photography books.

Some of these experiences left deep impressions. When asked which of the works on display I liked most, nay, desired to possess, the choices narrow to a few. Titian’s ‘Noli Me Tangere’ (1512) (Do Not Touch Me) of course. I have always been captivated by the dynamic use of diagonals – Christ, Mary Magdalen, the tree, the lovely warm light, Christ’s daring near-nakedness. You can feel the motion as he grabs the shroud to prevent Mary pulling on it. It is hard to conceive of a more perfectly balanced composition and if you think you cannot get away, as a photographer, with lampposts growing out of people’s heads, well just look what Titian did with that tree!

I have always felt that The National Gallery has way over-restored its Titians to near-Cibachrome color intensity, and that clearly shows here, but the magic of the picture saves the day.

So when it comes to lessons in composition, just check a few Titians out.

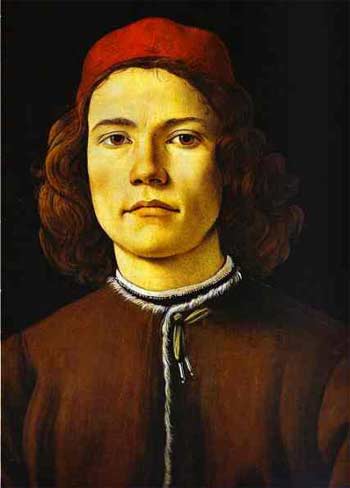

Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man (1485) is simply arresting. It’s one of the smallest paintings on display at 16″ by 12″ – the size of a regular photographic print. But you walk into that gallery and there’s only one thing you can see. The certainty of the gaze, the confident bearing, the red cap accent, the somewhat rushed rendering of the tunic, all to good purpose. It places all the focus on the eyes. When I first saw this – I was probably fourteen at the time – I made such a bee line for the picture that I nearly knocked over one of London’s dowager ladies in my rush. It’s that good. I frequently fantasized about pinching this masterpiece – how hard would it be to make off with a 16″ by 12″ canvas, after all? To this day the use of daylight and the way shadows model the face leave anything Vermeer did with lighting in, well, the shade.

As a photographer it is simply impossible not to like Caravaggio. Versions of The Supper at Emmaus hang in both the National Gallery and the Louvre, the diners’ ragged clothing rendered just so, the worms in the fruit on the table and, of course, Caravaggio’s signature lighting. But great as that painting is, it is simply eclipsed by The Conversion of Saul (St. Paul). In London’s Swinging Sixties the 21mm lens on a 35mm camera was de rigeur for any self respecting trendie. You saw its abuse everywhere, especially on record sleeves of the more extreme rock groups. Wild perspective, severely receding lines, objects very close to the lens, distortion galore. Well just take a look at this. Caravaggio had the 21mm figured. What is breathtaking about this canvas is how little space he has worked in. Painted in 1601 the canvas is simply enormous – some 7 1/2 by 6 feet. In other words, the horse is rendered at almost life size. Why so large? Caravaggio was a student of perspective. He knew that viewers would get too close to the painting, but that, by doing so, the grandeur of his ultra-wide angled vision would be correctly rendered and the perspective distortion would disappear. And so it does. The painting is immensely involving. You are there. Like a movie in a theater compared to the same thing on television, you have to see this live. Not reproduced.

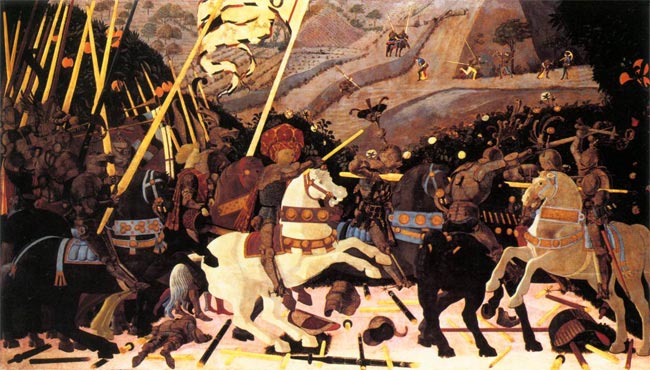

But easily the strangest use of perspective on view in The National Gallery belongs to a visionary whose work preceded that of all the above, none other than Paolo Uccello. In 1450 he painted three enormous panels depicting the battle at San Romano in which the Florentine army defeated Siena some twenty years earlier. The three panels are some 6 feet by 10 feet in size. One (the weakest, and that’s a cruel critique) hangs in The National Gallery. The others hang in the Louvre and the Uffizi. Fitting that three of the greatest masterpieces of the early Renaissance should hang in the three greatest Renaissance collections.

Appropriately, the best hangs in the Florentine collection, but look, if you gave me the one in London I would have no issues with finding wall space for it. I assert that there is more to be learned, as a photographer, from this one painting than from any number of academic studies on the use of perspective. By the time this painting was made, artists understood the rendering of perspective well. Uccello just chose to disregard the rules, dramatically foreshortening perspective, predating surrealism by some six hundred years. The repeating motif of the lances, the purposeful abuse of sizing (look how small the dead soldier in the left foreground is), the steep, tilted, climbing background with the horsemen rendered way too large, the detritus of battle painted in seemingly random perspective. It’s magic. Simply the greatest lesson in the (ab)use of perspective on canvas.

As photographers, we have a lot to learn from the masters.

And no, I harbored no fantasies about making off with the Uccello. It’s just too big to stash under a genuine English raincoat.