The 18th tee at sunset.

The clubhouse beckons.

iPhone 12 Pro Max snap.

The 18th tee at sunset.

iPhone 12 Pro Max snap.

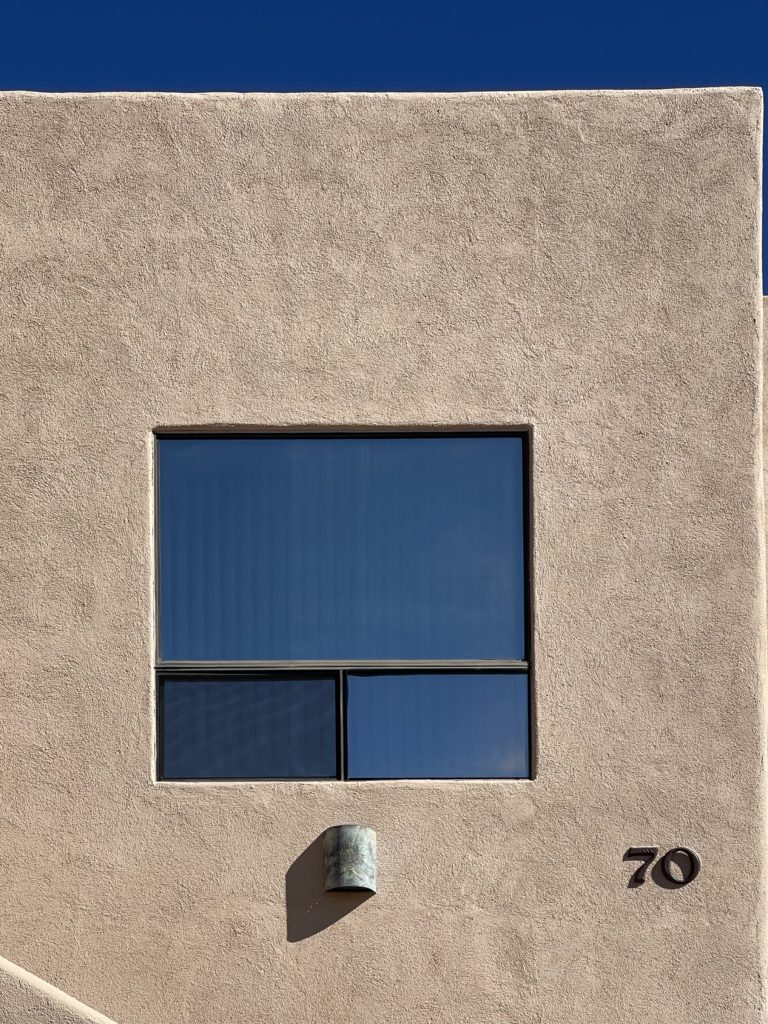

Rectangles, with a slant.

iPhone 12 Pro Max

A spot of wrenching.

One of the greatest joys of acquiring a new vehicle is the that of fixing the many things that need fixing. ‘New’ as in ‘new to me’ as I never buy new. I prefer to let someone else pay the 50-75% depreciation.

So when the Honda Silverwing maxi-scooter joined the stable recently, for the stunning sum of $3,250 with just 13,500 miles on the odometer, the first acquisition was the Factory Shop Manual, and I don’t mean some useless PDF version. Only paper manuals cut it for the serious mechanic and I was lucky to track down one of the few new ones left, the scooter last being imported to the US in 2013.

Hundreds of pages thick, the manual testifies to the complexity of a fuel injected, electronic ignition motor with linked ABS brakes and an automatic transmission. Mercifully the scooter is made in Japan, not Germany, with all that implies for the best design and quality control on the planet.

The only issue with this manual is with the circuit diagrams. While I have long known that electricity is the work of the devil, I also believe in ‘better the devil you know’, and that means having something I can read when messing with the circuitry. And the small print of the circuit diagram in the manual means it’s not useable.

However, it was a moment’s work to cut out the page from the manual, scan it and print it with SplitPrint which makes child’s play of printing something small over as many pages as you need – six in my case:

I needed a decipherable circuit diagram to permit installation of the greatest single motorcycle safety device on the planet – a headlight modulator. I have run one on my 1975 BMW Airhead for over two decades now and there is no better weapon to make SUV driving Psycho Mommy, with Little Johnny being rushed to his fifth activity of the day, sit up and take notice while fixing her hair and gossiping on the cell phone. Kisan tech has looked after me all these years and the device is 50 state legal. I keep a copy of the law in the glove compartment in case Officer Plod is on a sugar high from his third doughnut of the day and has forgotten the basics of the law.

The device is inserted between the high beam bulb and its base. A separate daylight sensor is installed to ensure no modulation occurs at night, in compliance with the law. The flashing headlight may be a nuisance to car drivers, but being seen beats being dead.

However, the opening for headlight replacement is designed strictly for ultra petite Asian hands so the whole front fairing had to come off to grant access:

Interposing the Kisan modulator in the headlight circuit is trivial. What actually dictated the need for the readable wiring diagram was the wiring in of a USB socket/voltmeter into the left glove compartment to provide power for an iPhone. I tapped into the circuit of the low beam bulb which is always on, switched with the ignition key. Here is the dual USB socket/voltmeter, neatly installed:

The next task was to change the engine oil and filter (replacing the chintzy aftermarket one with OEM), the coolant (the scoot is liquid cooled), the brake fluid in both brake circuits and the all important drive belt:

The Silverwing uses a gearless Continuously Variable Transmission with a Kevlar drive belt riding on two pairs of conical pulleys. As the throttle is worked these expand or contract, changing the gear ratio between the motor and the rear wheel, a system invented in the 1960s by the Dutch for their Daffodil cars. Had they named these the Tiger or Lion they may have sold in the US. In the event, ‘daffodil’ was just too effete for the tattooed crowd. Honda made hay where the Dutch made failure. The belt has a life of 16,000 miles and while mine came with 14,000 on it, it was also 14 years old so common sense dictated replacement – see the lower right image above. It’s made by Mitsuboshi in Japan, Mitsubishi’s long lost brother with a spelling problem. It’s actually a very easy job, made easier with the use of an air wrench to remove that stubborn front pulley retaining nut. And while the belt is off, the rear drive oil is easily replaced along with the sponge final drive filter – both oft neglected tasks.

Tires were next. That small contact patch on a two wheeler is vital to safety and the date codes on the Bridgestone tires disclosed them to be eight years old, even though only 60% worn. I like to remove my wheels and take them to the tire place not so much for reasons of frugality but because I do not trust a guy who works on agricultural Harleys to have either the expertise or caring to do the job right on a sophisticated machine.

Rear tire replacement is labor intensive, as a disk brake is used. This means the exhaust, rear brake caliper, parking brake caliper (yes, there’s a parking brake!) and swingarm all have to come off before the wheel can be pulled off. And when it came to removing the swingarm, corrosion had done its thing and the use of a three legged puller, straight out of the Spanish Inquisition, was called for:

It’s always something with old machines. Fortunately removal of the front wheel is easy, requiring removal of the axle – one nut – after freeing up the two pinch bolts.

Replacement of the air filter was next and boy, was the sake ever flowing when Honda’s design engineers came up with this design. It takes me 15 seconds to remove, clean and reinstall the air filter in the clothes dryer. The same task on the Silverwing takes an hour after you have removed the rear yoke (4 bolts), the rear decorative plate (2 screws), the right footpeg (2 bolts), and the right body panel (2 screws). Then you have this:

Yup. Count ’em. One dozen screws to remove the cover.

Then one more screw and the filter is replaced:

With USB power to hand for the iPhone, it was next necessary to craft a centrally mounted iPhone mount. Side mounted handlebar mounts do not cut it, so I procured a RAM mount and mounting ball, replacing the handlebar cover retaining bolts with a home made plate to mount ball and mount on:

RAM mounts have a great reputation and there is no way the iPhone is going to fall out. The red arrow denotes the sprung upper retainer, the green the fixed side motion limiters. This is the ‘large’ RAM mounting plate and easily accommodates my iPhone 12 Pro Max, even with a metal protective ‘bumper’ installed.

That plate is mounted on neoprene bumpers, heeding Apple’s recent warning about excessive vibration destroying iPhone cameras, though I do believe their message was aimed at pigs on Harleys. The counterbalanced, parallel twin in the Silverwing is the smoothest motorcycle I have yet ridden.

Ergonomics came next, the Silverwing’s low 29.1″ seat height meaning that my feet were far too high, causing back pain. As the floorboard height on a scooter is not adjustable this means that the seat had to be raised, which was accomplished with a water inflatable seat pad with a foam garage kneeler below, for a rise of some 3.5″. Now I could look over the tall windshield and the back pain was gone:

On cold days I ride with a heated vest, a lifesaver which requires a high current connection to the bike’s battery. If your kidneys are warm the rest of your torso will follow. There is no battery power take off on the Silverwing but after rooting about in the lower left of the bike I found a handy unused flange with two tailor made bolt holes. It was a matter of moments to craft an aluminum plate to attach to these, with a large hole at the other end for the robust Hella socket, wired directly to the adjacent battery:

Now the heated jacket can be plugged in to the conveniently located, unswitched socket behind the rider’s left leg.

Body damage? There were a couple of spots where the paint had been scratched, easily remedied with matching touch-up paint from Colorite. The lower left skirt was badly scratched and cracked in one place:

Outlay of the modest sum of $50 saw a new replacement; I have never found repairs to cracked plastic to last in the hostile setting of a motorcycle. Total overhaul costs – new tires, new drive belt and the body panel – ran under $600.

One final touch was called for, a riser for the seat back rest to position it strategically. Here is the result:

She’s now ready to ride!

A sad anniversary.

Steve Jobs died ten years ago today.

Here’s the tribute from his chief designer, Jony Ive:

The power of curiosity, the desire to learn rather than to be right, the willingness to take risk. All the dictates for a successful life are there.

You can see my picture taken on the last day of the life of a great man here.

Long lived bird.

Spotted in a local store, the owner told me the African Grey’s life expectancy is some sixty years.

iPhone 12 Pro Max snap, long lens.