What really matters when choosing a camera?

Twenty years ago I used three cameras most of the time.

A Leica M3, a Rollei 35 and a Rolleiflex 3.5F. You could not find three more different pieces of equipment, with fitness for purpose dictating that there should be three rather than one.

While I’m not that sure about the level of objective analysis which went into the buying decision, now that I think it through there were just five criteria dictating the choice of each. Those same five criteria apply today, though now I manage to get by with two cameras rather than three.

They are:

- Speed

- Bulk

- Noise

- Definition

- Price and it’s bedfellow, fear.

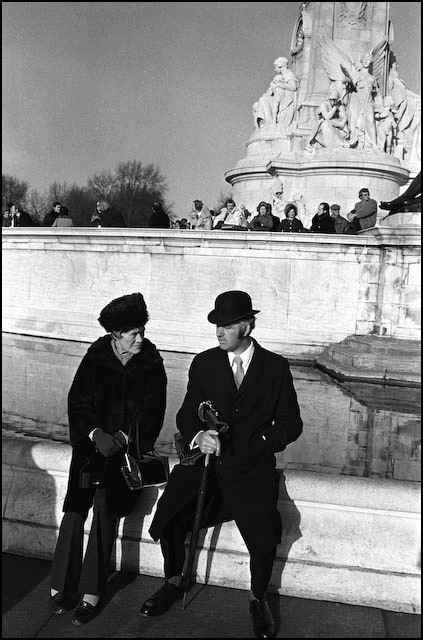

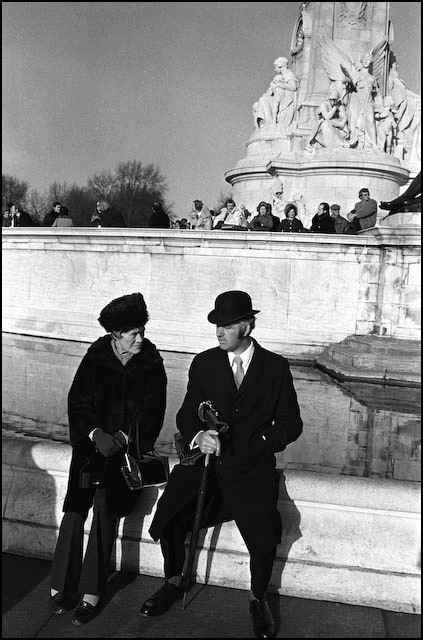

British and proud of it, 1976. M3, 35mm Summaron, TriX.

It’s useful to keep these in mind when making the buying decision.

Speed means speed of operation. Back then the Leica was the street shooter without equal. A flip of the thumb advanced the film, the shutter was quiet (if not as whisper quiet as blinded Leica worshippers would have you believe; for that listen to a twin lens Rolleiflex), lens changes were fast and you were generally unobtrusive thanks to the blisteringly fast manual rangefinder focusing.

Bulk is an issue if you travel a lot and for that the Leica, small as it was, was simply too bulky. That’s where the Rollei 35 came in, with its collapsible lens, silent shutter and barely larger than a film cassette or two. Mine traversed the world many times and served me well, after the obligatory breakdown out of the box. Rollei’s Singapore craftsmen had yet to learn about quality control.

Noise and unobtrusiveness go hand-in-hand for the candid photographer, so the Leica’s quiet shutter did the trick.

Definition and freedom from grain became issues with any Leica enlargement greater than 8″ x 10″. For large smooth areas of sky or skin you had go to the next negative size, which came with the Rolleiflex 3.5F, maybe the finest camera ever to leave the factory of Franke & Heidecke. 16″ x 20″ (that was ‘big’ back then) was no problem with the Rollei TLR.

Price and fear are bedfellows. The Leica was expensive, the lenses more so, and you were always scared of getting mugged, whacked or otherwise resented or abused. Once the Japanese SLRs took over the 35mm market the fame of the Leica – and hence the ability morons had to recognize it – faded and with it the Fear quotient. But it was always there. Not for one moment did I care if someone pinched my Rollei 35 and the 3.5F was pretty much a studio camera.

These thoughts came to mind in discussions with a friend whose Canon Digital Rebel finally gave up the ghost and for which an urgent replacement was needed. Now this friend does the occasional wedding – surely there can be no field of photography more greatly imbued with the fear of failure – yet reliability simply did not come up in our talks, any more than it features in the list above. Bottom line is that all the better cameras from the big names are reliable in all but combat conditions. Rather, the focus of our discussion was on noise. You simply cannot have a DSLR machine-gunning away in a quiet church where a sacred ceremony is underway. When all was said and done, my friend opted for Canon’s 40D which would both take her existing Canon lenses and offers a ‘silent mode’ in Live View whereby the mirror is moved out of the way and the LCD becomes the viewfinder. Not ideal as LCD viewfinders are genuinely awful, but when you hear how quiet the shutter is in this mode you might well conclude that the trade-off makes sense.

When buying my 5D I was much more studied about what I wanted than in days past. And because I no longer wanted to mess about with clunky medium format gear, I wanted the best possible definition out of a smaller package. On the other hand, I realized that small size was not consonant with that dictate, so my choice was pretty much limited to full frame digital. Further, I wanted my wide lenses wide, not cropped. Cropped sensors have improved greatly since then but 30 months ago the difference between Canon’s cropped and full frame sensors were significant, not least in their ability to hide noise at higher ISO settings. One look at the definition of the images, aided by some good, realistically priced lenses from Canon, suggested that the 5D could replace both 35mm and medium format film, and such proved to be the case. The ease of use of a 35mm SLR with the definition of medium format film. Sweet. I bought one. It was only one of two full frame DSLRs available, the other being Canon’s very expensive 1Ds.

And I was no longer particularly fixated on street snaps which, in any case, had become much easier to make as cameras became ubiquitous. No one cared if you pointed a camera at them.

So my priority order for the Five Criteria had changed.

Originally it was as listed above. Now it was:

- Definition

- Noise

- Price and it’s bedfellow, fear.

- Bulk

- Speed

Definition was A Number One and Price now mattered – it irked me to have so much capital tied up in a hobby and I resolved to avoid that when changing equipment. Fear was not an issue – I stick black electrician’s tape over the obnoxious ‘Canon’ logos and go on about my unobtrusive way. Noise still mattered. The 5D is hardly ideal but it beats a Pentax 6×7 or a Rolleiflex 6003/6008, which sound like one of Krupp’s finest when they go off. Bulk worked out well. The 5D is not small but any time you get medium format film quality in a 35mm SLR package, buy it and run. Price never mattered. It’s not that I’m Rockefeller but judicious buying and a disciplined approach to life makes the price shock that much less noticeable. This is one of my key interests after all, not a passing fling. And as with Porsche drivers, you get two kinds – those who love the gear and those who can drive. I’ll let you decide which camp I am in.

But I still need two cameras. When it comes to something pocketable which can go anywhere I use the Panasonic LX-1. Sure, it has lots of limitations (needs a viewfinder, shutter lag, grainy/noisy images) but so did the Rollei 35. But it more than suffices in those times when you simply cannot haul the 5D around.

My two cents worth of advice suggest that you make a like list prioritizing your needs then choose the camera which is the best match. Forget about brands. The major makes offer so much choice that it does not have to be Canon or Nikon – just choose something that scores most on your short list of essentials. That way the noise of brand loyalty (a dumb idea if ever I heard of one) is silenced. And do not discount the idea of more than one camera. Horses for courses and all that.

Antiques, 2006. 5D, 24-105L, IS on, 1/30, f/6.3, ISO 200. Processed in Lightroom.