Stoopid is as stoopid does.

Update 9/2/2020:

Told you so!

Stoopid is as stoopid does.

Update 9/2/2020:

Told you so!

Back in the day.

There is no more need for folding cameras or for those with collapsible lenses. Modern iPhones give 99% of photographers more than they will ever need and we will see periscope zooms in small packages in a generation or two. Quality is unsurpassed for the designed display medium which is a laptop, and the technology superb.

But before the iPhone there were many attempts at crafting small bodies and these involved either retractable lenses or collapsible fronts, the latter approach generally requiring some form of light tight bellows. Here are some of the best examples of the genre.

The grandfather of collapsibles is the Leica, whose 50mm f/3.5 Elmar lens retracted into the already compact 35mm film body to craft a device which could (more or less) be slipped into a large suit pocket or into an overcoat. Leitz soldiered on with collapsible 50mm (and a 90mm f/4 Elmar) well into the M era (1954 on) and even the vaunted early 7-element Summicron came in a collapsible mount.

The hood made a nonsense of the concept and should be avoided. There was no interlock so if you forgot to extend the lens you would get a blurred blob in lieu of a picture. But the lens was decent (a 4 element Zeiss Tessar design ‘borrowed’ by Leitz), so long as you remembered to remove the lens cap.

A really clever variant, this one a folder, was the American Crown Graphic, much beloved of press men before smaller offerings came along. It took massive 4″ x 5″ negatives, was sharp as a tack and very light and compact given its capabilities, which included a tilting front and interchangeable lenses with rangefinder coupling. I found mine to be a delight to use.

The Crown Graphic was arguably a variation on the earlier Zeiss Ikonta which took 120 (2 1/4″ square) film and commenced manufacture in 1929, going through many versions with post-war models offering an excellent 75 or 80mm f/3.5 Tessar in a Synchro Compur leaf shutter. The Tessar used here was ‘better’ than that found on 35mm cameras for the simple reason that you did not have to enlarge the image as much when making prints. Truly compact when collapsed given the large negative size, this was one of the best high quality/small size cameras of the era.

Kodak had an excellent, if complex, set of offerings in their Retina series, all made in Germany, and culminating with the Retina IIC (no meter) and IIIC (uncoupled selnium cell meter), The front element was detachable allowing 35mm and 80mm converter lenses to be attached. These were gargantuan and the quality only so-so, but the base offering of the Rodenstock Heliogon or Schneider Xenon 6-element f/2 50mm standard lenses was excellent. The camera’s Achilles Heel was a pot metal rack for the base-mounted film advance lever which would strip with use:

Rollei came along with a stroke of genius in 1963 with the Rollei 35, whose ads correctly boasted that the camera was not much larger than a 35mm film cassette. The collapsible lens – with an interlock no less – was the time honored Tessar and a coupled CdS meter was included.

I travelled all over the world with mine and while focussing was by guess – there was no rangefinder – the results from the 40mm lens were excellent. Mine came in enameled black, making it pretty stealthy.

But the genius designers at Olympus were not to take this lying down and came up with something infinitely superior in their Olympus Stylus in 1991. It had autofocus for the 35mm f/2.8 lens, a length which was perfect for street snapping, and a flash was included. This was a clamshell design. Slide open the lens cover and the lens would extend. The camera was well made, housed in a tough resin shell, and I literally beat mine to death when it failed after many journeys and hundreds of rolls of film. Yes, the film rewound automatically at the end of the roll. One handed operation was a breeze and over 5 million were sold. I consider the Olympus Stylus the best collapsible camera made.

For the Man in you.

For an index of cooking articles on this blog click here.

The ‘Full English’ denotes the traditional English breakfast, one described in great historical detail, with regional variations, by Wikipedia.

Now that I have found a reliable source for smoked mackerel kippers (thank you, Whole Foods) I serve my son a Full English monthly, though I do drop the baked beans – there’s only so much a Man can take – and Winston is no coffee drinker.

I have so many pleasant memories of the Full English.

When a young lad – I would have been 14 or so at the time – in London, I got a summer job at the Habit Diamond Tooling Company. Their byline was “Make it a Habit” and they cranked out machine tools with diamond abrasives for industrial use. I was paid some $20 weekly – this was in 1965 – and was further provided with 5 Luncheon Vouchers. The face value was some 40 cents and yes, that got you a Full English at the local ‘caff’ with money left for a tip. And yes, it was absolutely delicious. The job was incredible fun and I learned to operate a pantograph, a lathe, a mill and an industrial grinder. The lessons garnered in working class attitudes were invaluable, and the many posters of buxom, undressed women on the walls of the factory harken back to a time when men were Men and women were in the kitchen. Or naked on posters.

British Railways used to serve a Full English on their sleeper trains from London to Scotland and it was absolutely delicious also, the kippers floating in a sea of butter. This was always preceded by a gentle knock on the door from the cabin attendant who woke you with an offering of tea, inviting you to the dining car. Another great tradition recently discontinued in a cost saving measure by a nation in terminal decline. Sad. A Full English on a train hauled by the Flying Scotsman was really something, as I can personally attest. (My eldest sister was an undergraduate at St. Andrew’s in Dundee, hence the Scottish trips. Plus, I love Scotland).

When I vacationed in Scotland before immigrating to the US in 1977, the Full Scottish would add black pudding or haggis. Once when overnighting at a B&B in the western Highlands I expressed dismay to the landlady on noticing how much larger my breakfast was than that of the young woman tourist staying in the same home. “Och no, lad” quoth she “Ye have tae go oot and work”. OK.

Anyway, here’s Winston contemplating his Full English the other day:

iPhone 11 Pro image processed in Focos.

A masterpiece of cinematography.

In his enthralling thriller of 1948 Rope, Alfred Hitchcock used the ‘One Take’ artifice to add spice to a story of two psychopaths who murder a friend for fun. A perfect John Dall leads a cast with Jimmy Stewart and Farley Granger in what purports to be a movie shot in one take. In practice a roll of movie film ran some 12-15 minutes back then and Hitch cleverly changes reels by zooming in on the back of one of the participants, freezes the frame, and inserts a new roll in the camera. It’s pretty seamless and coaxes the actors into stage quality performances as there can be no retakes.

British cinematographer Roger Deakins had no such constraints in the making of the 2019 classic 1917 whose two hour length is also shot in one take. And the result is positively hypnotic. Deakins is no stranger to readers of this journal and for an extensive survey of his work you should go here. After a multi-year Oscar drought – what are those Academy members thinking of? – Roger has now garnered two Oscars in as many years for his camera work, and looking at 1917 it’s hard to see how anything could compete. Here’s to many more Oscars for the master.

Pig enshrined.

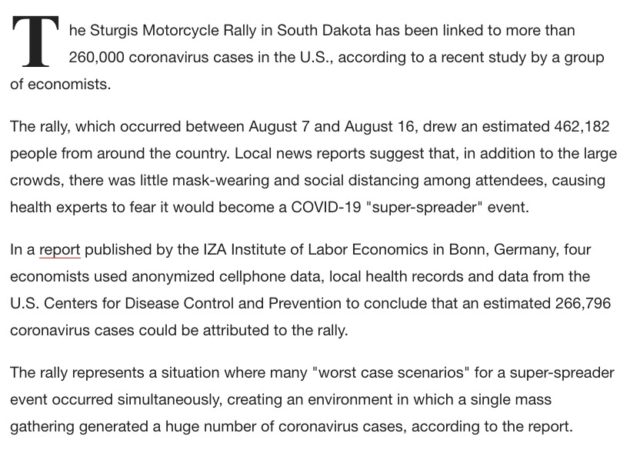

A photo is worth 150,000 lives.

Congratulation to Samuel Corum of the The New York Times for this piece of genius.

For Arnold Newman’s take on a mass murderer from an earlier generation, click here.